Baking Deep Dive: Caramelization & Maillard

From molecules to meaning

Introduction

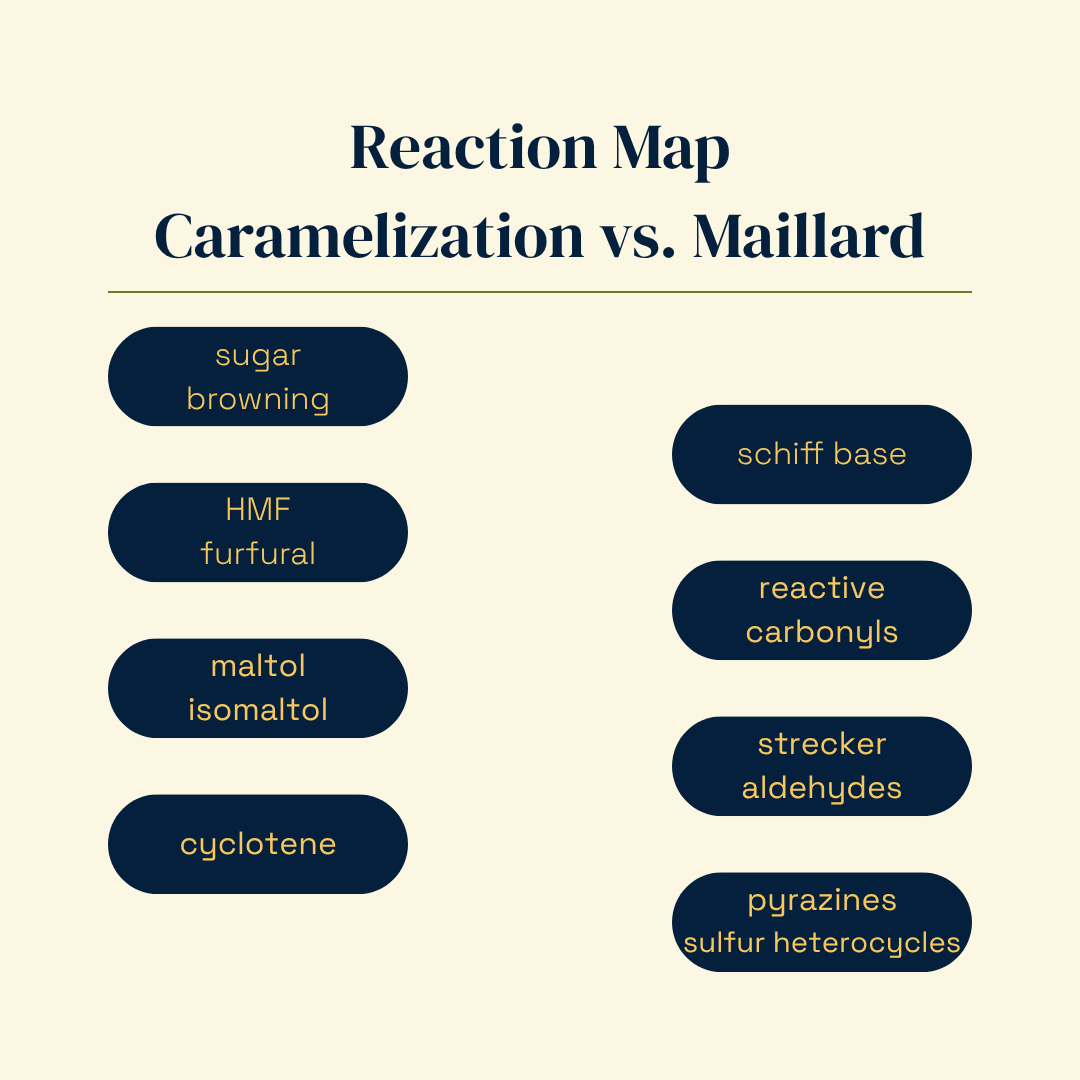

Baked flavor isn’t a single reaction, it’s two families of chemistry running in parallel and feeding each other. When people say “caramelized,” they often mean both caramelization (sugars alone) and the Maillard reaction (reducing sugars + amino groups). In the cup or on the plate, you experience that chemistry through the compounds it produces and their sensory signatures: sugar-browning furanones (maltol, isomaltol) and cyclotene → warm “brown” sweetness; Maillard-derived pyrazines and Strecker aldehydes → roasty/nutty/malty; trace sulfur heterocycles → deep roast.

We’ll stay chemistry‑first: which compound families each pathway produces, what those compounds smell/taste like, and how process choices bias those families (pH, aw, sugars, amino sources). The free section builds a shared vocabulary; the paid section supplies natural‑only 100‑part base structures (Baked Cookie, Caramel) with dose ranges you can adapt to your matrix.

Caramelization (sugars only) → maltol/isomaltol, cyclotene → caramel/brown.

Maillard (sugar + amino) → pyrazines, Strecker, sulfur → roasty/nutty/malty.

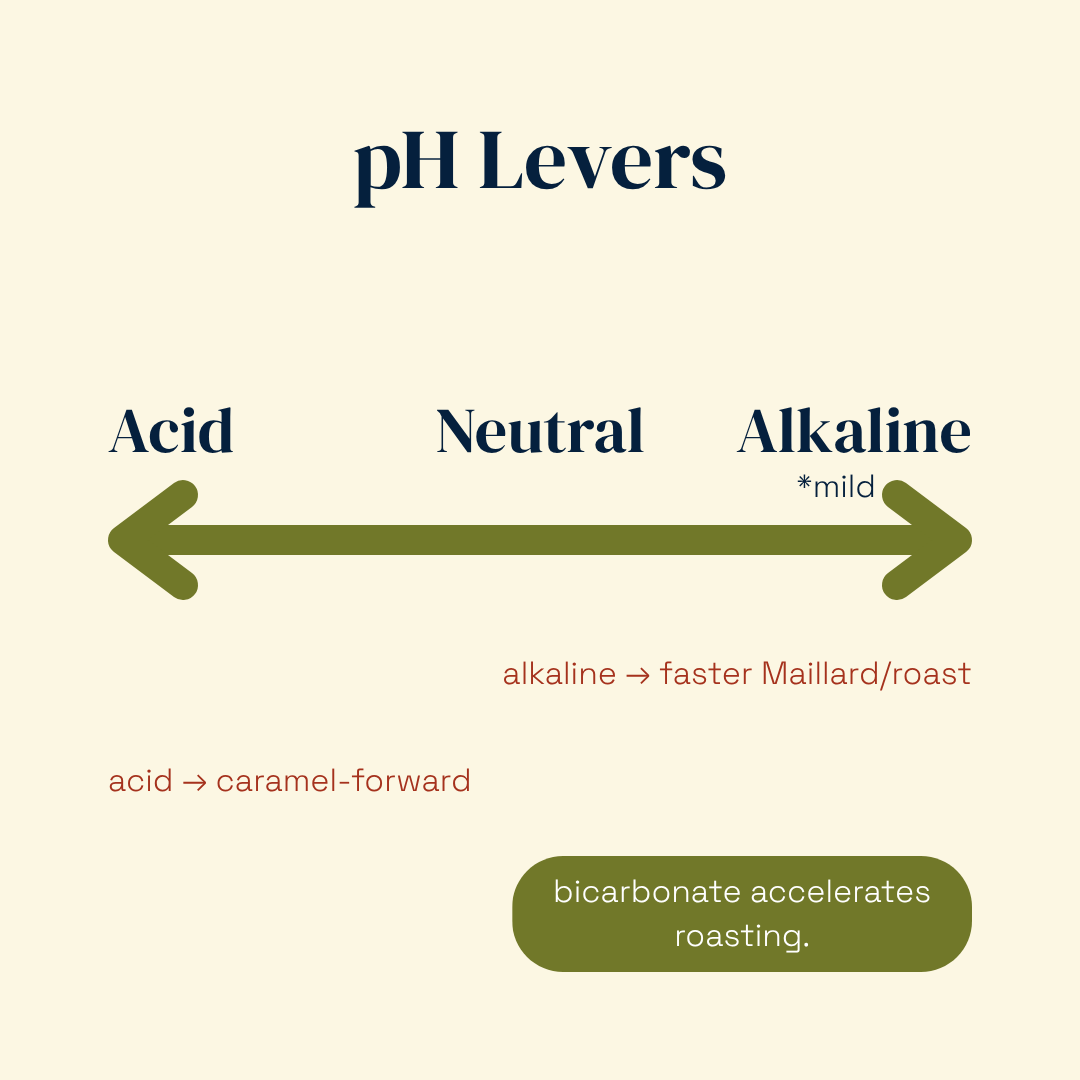

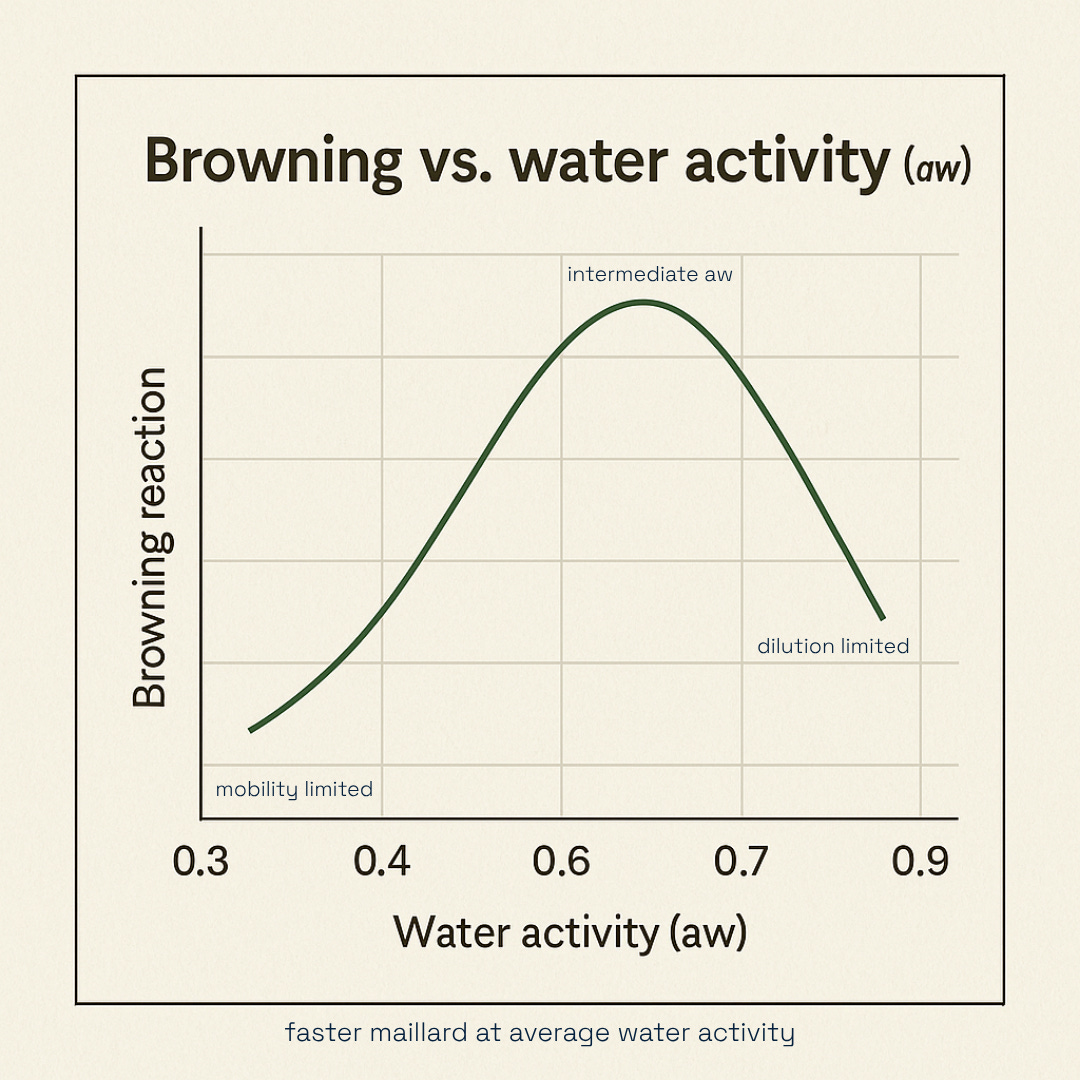

Steer with pH (alkaline → roast) and water activity (aw) (mid-aw → faster Maillard).

What you’ll learn (free)

The difference between caramelization (sugars only) and Maillard (reducing sugars + amino groups) and why both show up in baked flavors.

The key intermediates and aroma families generated along each path (furan/furanones, maltol/isomaltol, diketones; pyrazines, Strecker aldehydes, sulfur heterocycles).

The process levers that drive browning and aroma: temperature, time, pH, water activity (aw), sugar type, amino acid profile, fat/dairy solids, and oxygen.

What you’ll learn (paid)

A bench‑ready way to link compound families to sensory readouts (e.g., furanones → brown sugar/caramel; pyrazines → roast/nutty; Strecker aldehydes → malty/bready).

How to identify compound families and odor relationships; detailed odor thresholds and the full matrix.

Practical Baked Cookie and Caramel flavor base structures, matrix‑specific use‑rates, and a bench ladder as well.

Two pathways, two toolkits

Caramelization (sugar‑only browning)

Caramelization, in short: Sugar browning that yields maltol/isomaltol, cyclotene, and caramel color.

What it is (mechanism): Thermal dehydration, isomerization, fragmentation, cyclization, and polymerization of sugars without amino acids. Some sugars briefly shift into a more reactive form and then lose water (dehydrate) to 5‑hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF); five‑carbon sugars analogously make furfural. Further rearrangements/fragmentations form small carbonyls (e.g., diacetyl, acetoin, acetaldehyde) and cyclic “browners” like maltol/isomaltol (3‑hydroxy‑2‑methyl‑4‑pyrone family) and cyclotene (methyl‑cyclopentenolone). Progressive polymerization gives brown pigments (often grouped as caramelan/caramelen/caramelin).

Why conditions matter: Acid pH tends to favor HMF/furfural formation; mild alkalinity accelerates fragmentation and darkening. Lower water activity after surface drying speeds these pathways; metals can catalyze sugar breakdown.

What it makes (aroma): Furan/furanones (HMF/furfural context; maltol/isomaltol character), cyclotene (brown/maple), and small esters/ketones (e.g., diacetyl) that read as buttery/volatile top notes.

What it makes (color/body): Higher‑mass brown polymers (caramelan/caramelen/caramelin) that deepen color and add thickness/body.

Quick definitions (caramelization):

HMF: 5‑Hydroxymethylfurfural, a dehydration product of hexoses; brown, caramel‑like nuance and color precursor.

Maltol / Isomaltol: Pyrone‑type compounds that smell like cotton‑candy/caramelized sugar; useful as “brown” extenders.

Cyclotene: Methyl‑cyclopentenolone; maple/licorice‑like warm brown note.

Maillard (amino‑carbonyl browning)

Maillard, in short: Sugar + amino chemistry that yields Strecker aldehydes, pyrazines, sulfur heterocycles, and crust color.

What it is (mechanism): Carbonyl of a reducing sugar reacts with a free amino group (from amino acids/peptides/proteins). The first step is Schiff base formation — a temporary sugar‑amino link (an imine, C=N). Then it rearranges into a more stable sugar‑amino form (Amadori/Heyns product, a ketoamine). These intermediates break into highly reactive small carbonyls (e.g., glyoxal, methylglyoxal, diacetyl) that drive the rest of the flavor chemistry.

Key cascades & products:

Strecker degradation: α‑dicarbonyls react with amino acids → Strecker aldehydes (+ CO₂ + amines). Examples: leucine → 3‑methylbutanal, isoleucine → 2‑methylbutanal, valine → isobutanal, methionine → methional, phenylalanine → phenylacetaldehyde.

Heterocycle formation: Condensations yield pyrazines (roasted/nutty), pyrroles/pyridines, and sulfur heterocycles (thiazoles/thiophenes) when cysteine or thiamine is involved. Signature notes like 2‑acetyl‑1‑pyrroline (roasty/popcorn, very potent) arise under low‑moisture heat with appropriate precursors (e.g., proline/ornithine + lipid oxidation products).

Polymerization: Advanced products assemble into brown, high‑molecular‑weight melanoidins (color + antioxidant activity), which also bind/entrain aroma.

Why conditions matter: Mildly alkaline pH speeds the initial condensation and downstream steps; intermediate water activity maximizes mobility; heat accelerates every stage but can push into burnt/phenolic if overdone.

What it makes (aroma): Strecker aldehydes (malty/bready/potato‑like), pyrazines (roasty/nutty), pyrroles/pyridines, sulfur heterocycles (deep roast), and signature notes like 2‑acetyl‑1‑pyrroline.

What it makes (color/body): Complex melanoidins and linked flavor precursors that signal “baked/crust.”

Quick definitions (Maillard):

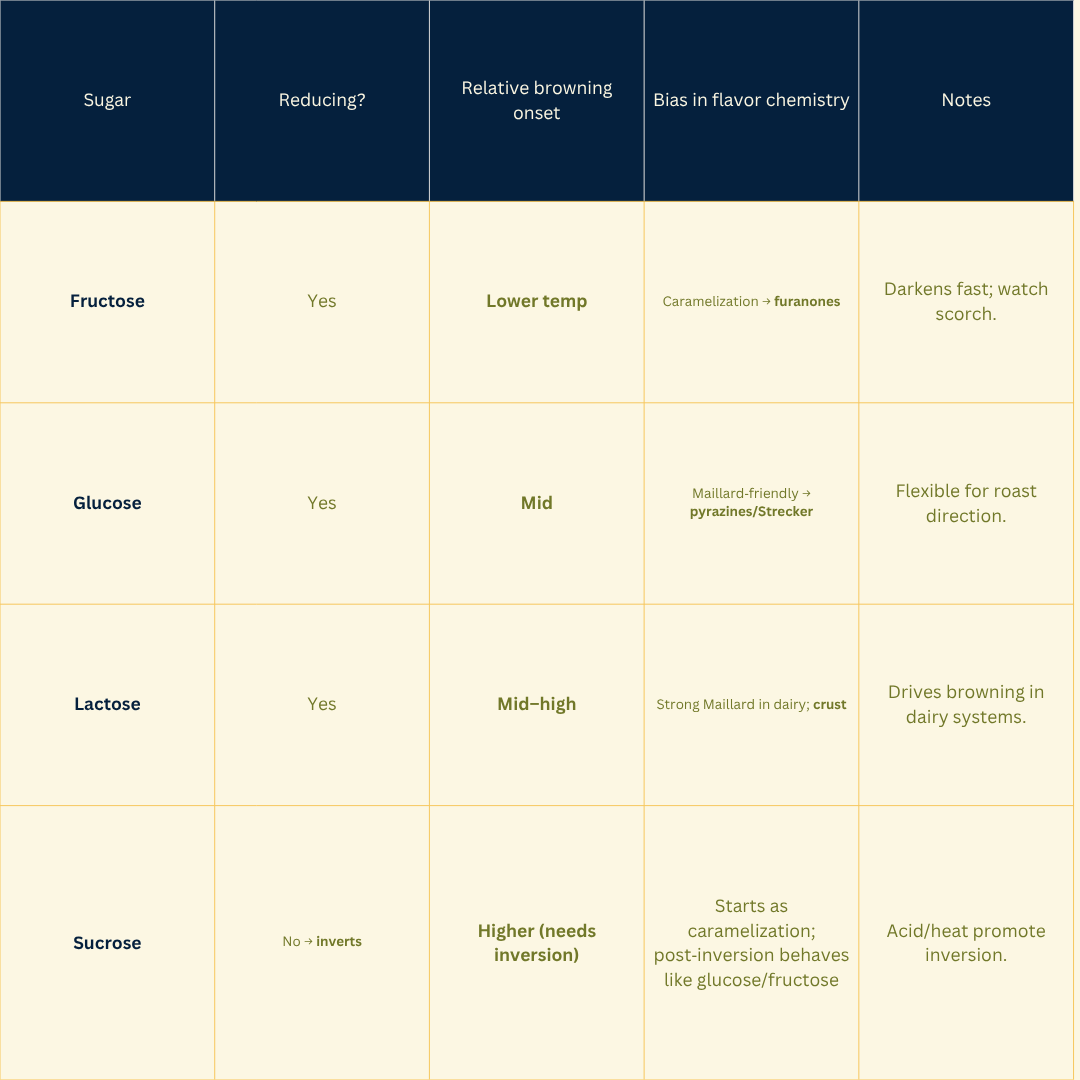

Reducing sugar: A sugar that can open to an aldehyde/ketone (e.g., glucose, fructose, lactose). Sucrose is non‑reducing until it inverts.

Schiff base: The initial imine formed when a sugar carbonyl reacts with an amino group.

Amadori/Heyns products: More stable ketoamine (aldose route) or amino‑aldose (ketose route) rearrangement products that feed later steps.

Strecker degradation: Reaction of α‑dicarbonyls with amino acids yielding Strecker aldehydes that smell malty/nutty/bready.

Melanoidins: High‑mass brown polymers formed late in Maillard; deliver crust color and can trap aroma.

Why both matter together: Baked cookies, crackers, breads, and caramels rarely involve a single pathway. Caramelization adds warm sugar/cotton‑candy/caramel and color; Maillard delivers roasty/nutty/baked identity. Your levers decide which path dominates.

Process levers that actually move flavor

Temperature & time (macro control)

Caramelization thresholds rise with sugar type (fructose < glucose < sucrose); meaningful aroma starts once water is driven off and surface temps climb.

Maillard accelerates rapidly with heat; time–temperature abuse pushes harsh/burnt phenolics and elevates off‑targets.

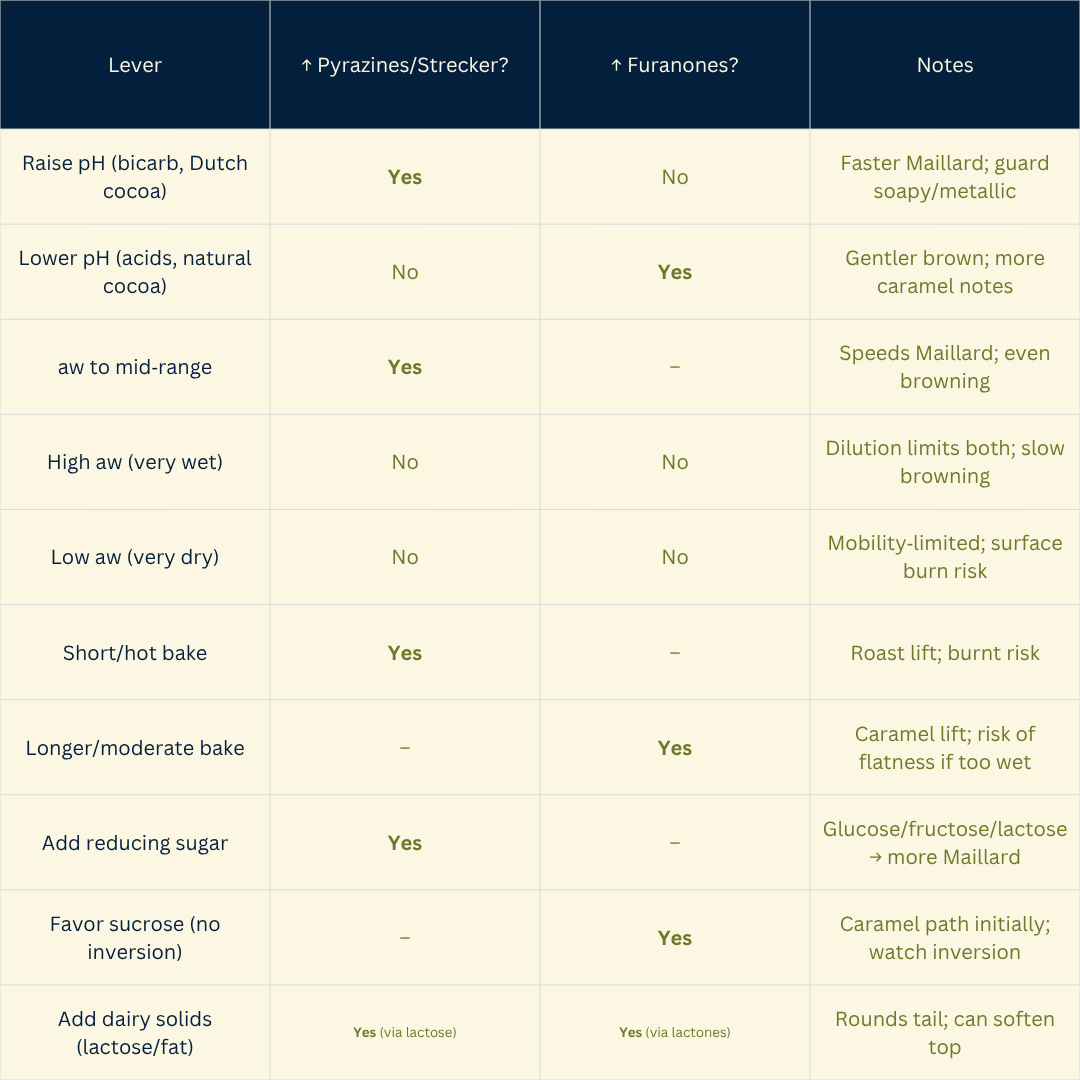

Design cue: Link process levers to compound families — alkalinity + mid‑aw → more pyrazines/Strecker (roasty/nutty); acidic conditions + longer dwell → more furanones (caramel).

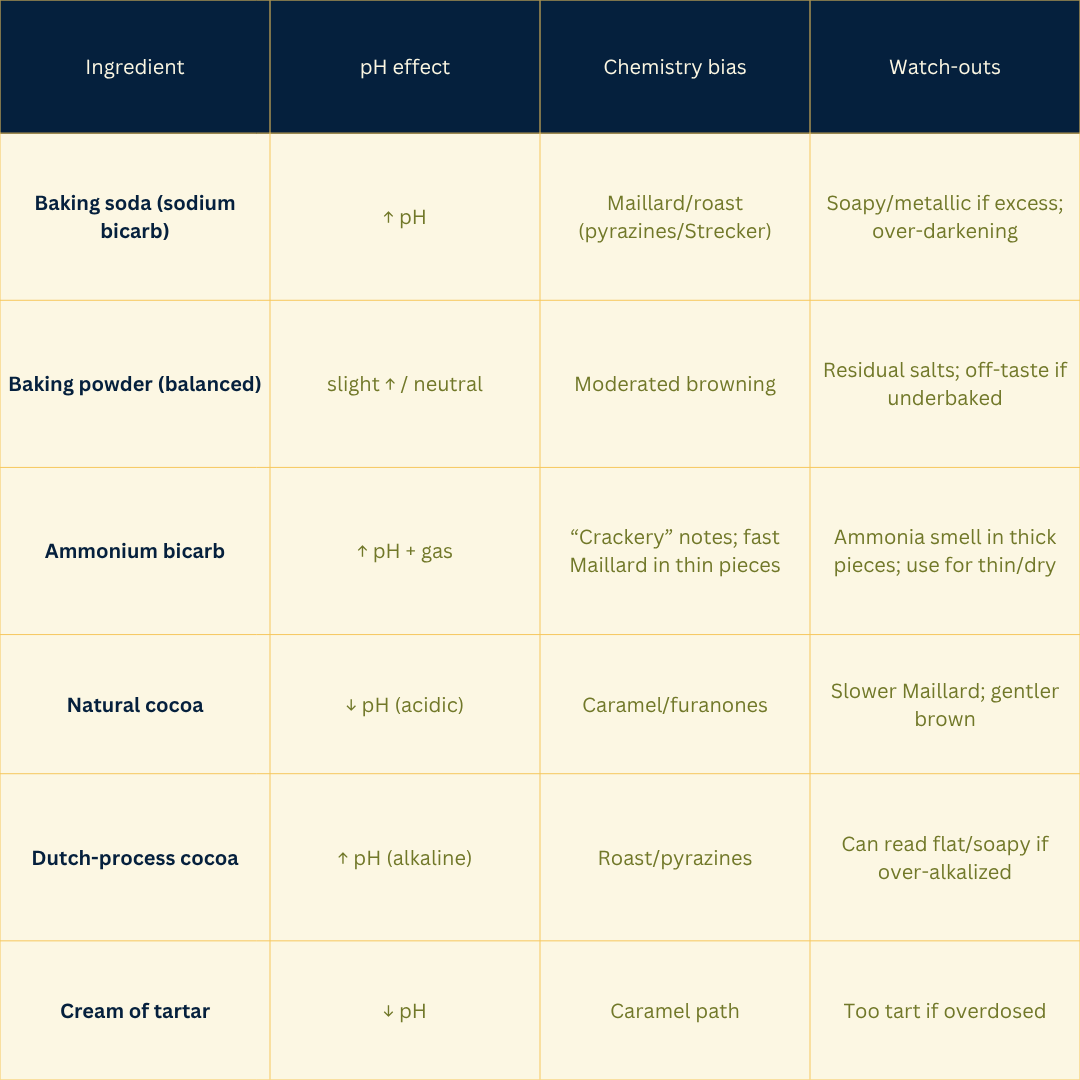

pH (alkaline = faster Maillard)

Higher pH makes amino groups more reactive and speeds Maillard (bicarb/alkalized doughs → roasty/nutty).

Acidic systems favor caramelization cues (furanones) and can mute pyrazine formation.

pH: Fastest control knob, flip caramel ↔ roast without changing hero ingredients.

Water activity (aw) — the browning “sweet spot”

Maillard runs fastest at intermediate aw; too dry and mobility drops; too wet and reactants dilute.

Practical read‑across: cookie doughs with moderate solids and controlled moisture brown more evenly and develop cleaner baked notes.

aw: Clean color, faster, aim mid-aw to avoid burnt edges with pale centers.

Sugars & amino profile

Reducing sugars (glucose, fructose, lactose) fuel Maillard; sucrose must invert first.

Amino acid choice matters: leucine/isoleucine → malty/nutty aldehydes; methionine → cooked‑potato/malty; cysteine + reducing sugars → potent sulfurous roast (tiny doses).

Sugars: Choose your path, reducing sugars push Maillard; sucrose needs inversion, so it starts more caramel-forward.

Fats & dairy solids

Milk fat and thermal oxidation yield lactones (buttery/creamy). Lactose (reducing) promotes Maillard in dairy‑containing doughs.

Butter handling (clarified vs whole) and water removal affect both browning rate and volatile balance.

Leavening, salts & trace minerals

Bicarb raises pH → faster Maillard; ammonium bicarb contributes crackery notes.

Salt shapes perception (bitterness suppression, sweetness contrast) and ionic strength; trace phosphates influence pH/complexation.

Hardware & geometry

Heat transfer: conduction (sheet), convection (fan/air), radiation (upper elements) change browning patterns.

Surface‑to‑mass: thinner pieces brown faster; docking/score lines influence moisture loss and aroma.